Sometimes The Shark He Go Away

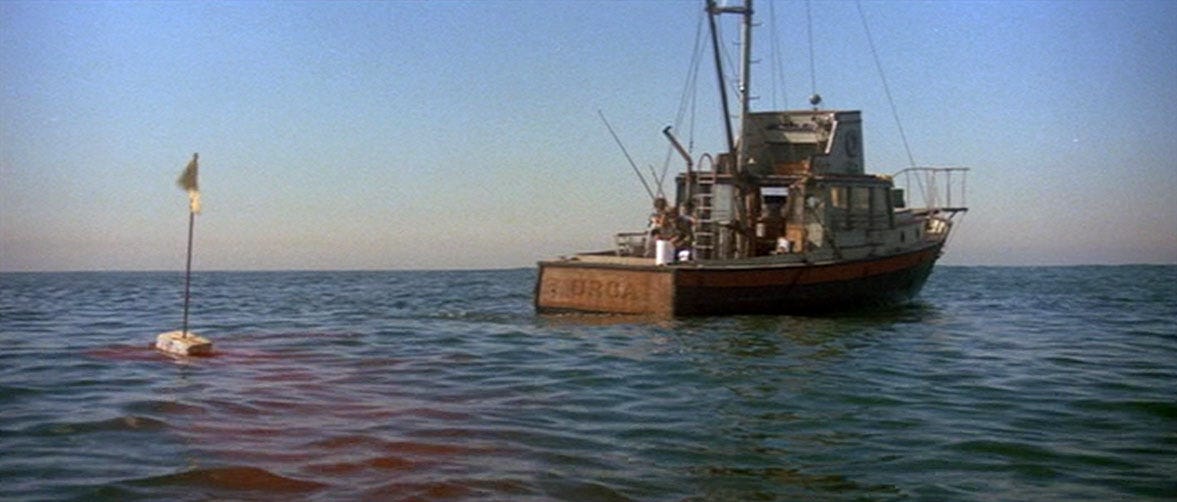

The real message for me behind Spielberg's single greatest scene, and how it might be the best way that I can explain how my brain works.

‘Jaws’ first premiered in theaters across America fifty years ago this weekend. To celebrate this milestone of an American classic, we present an early piece from the WAIM Archives that features my interpretation of director Steven Spielberg’s single greatest scene.

This piece is from the What Am I Making Archives. It was first published on April 5, 2023. This version has been lightly updated and edited for this posting.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to What Am I Making to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.