Our Musical DNA No Longer Adds Up

Music was once seen as a vital tool, and was used as a way to build literal civilizations. Now, it's virtually worthless.

This piece is from the What Am I Making Archives. It was first published on January 10, 2025. This version has been lightly updated and edited for this posting.

In 2008, in the mountains of southern Germany, researchers found pieces of a flute that had been crafted from a vulture bone. The instrument featured five holes and a mouthpiece. It measured nearly 13 inches long and was just .03 inches wide. The flute was found in a Stone Age cave with a series of fragments from other primitive flute-like instruments. After extensive research and carbon dating, it’s estimated that the flute is approximately 40,000 years old, pushing our musical history back much further than had previously been thought.

Researchers at the University of Tübingen in Germany were not just interested in the musical quality of the flutes, they sought to understand more deeply what role music might have played in these early societies. According to the team, it is very likely that the use of music was a way for these tribes and groups to gain a societal advantage. The researchers at Tübingen believe that these ancient flutes are evidence for an early musical tradition that likely helped these societies communicate and form tighter social bonds.

For our earliest ancestors music was not just entertainment, but also a societal advantage and a tool for literal survival.

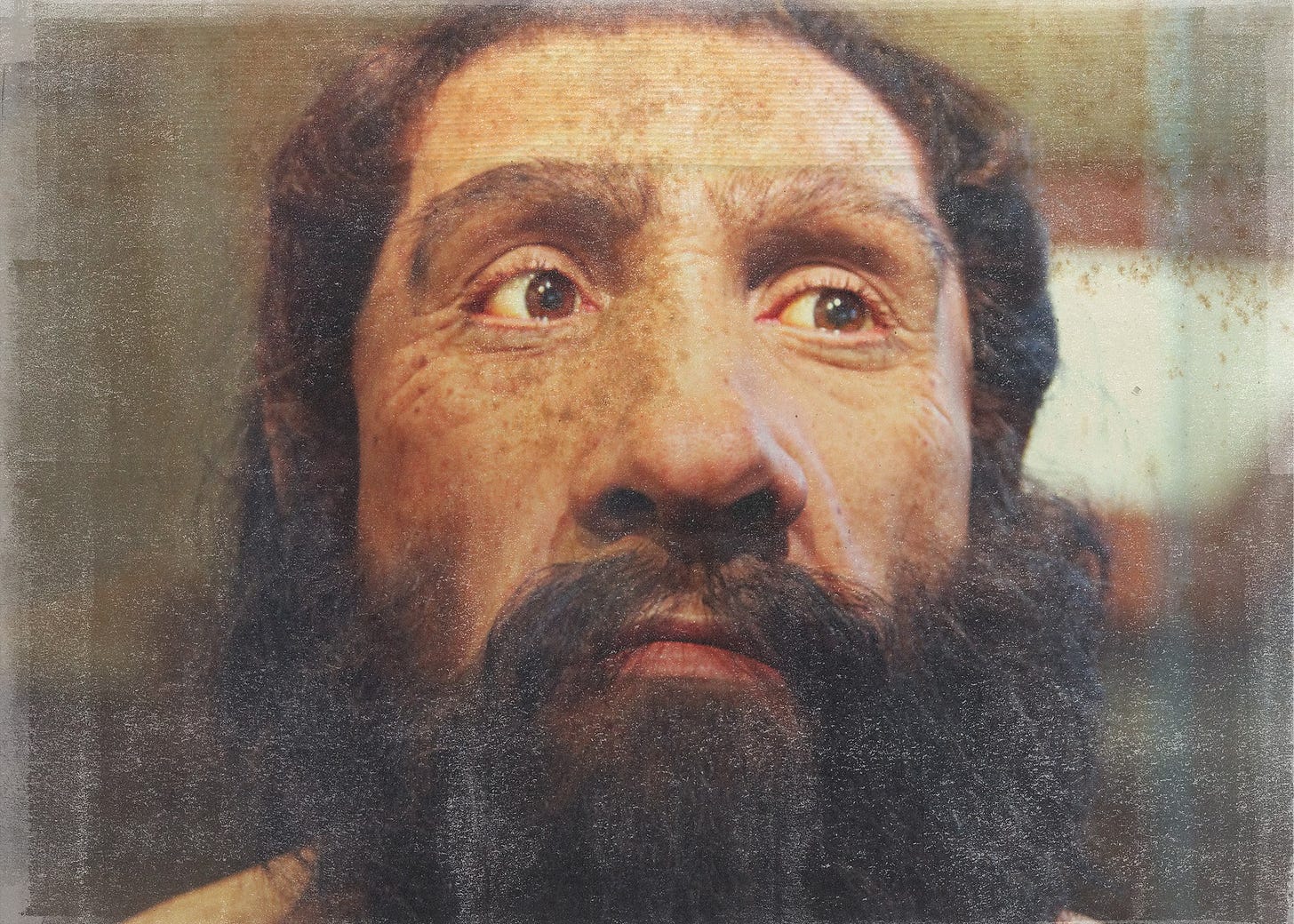

Long before our ancestors learned to forge flutes, they almost certainly used their own voices as instruments. Steven Mithen, archaeologist and author of The Singing Neanderthals suggests that Neanderthals may have sung in “HMMMM” phrases as a way of communicating in an era before shared language. Music has played a central role in our evolution from the earliest days of our budding humanity.

The evolutionary psychologist and author Geoffrey Miller suggests musical displays may also play a role in “demonstrating fitness to a mate.” Based on the ideas of honest signaling and the handicap principle, Miller has suggested that music and dancing, as energetically costly activities, demonstrated the physical and psychological prowess of the singing and dancing individual. A potential mate who could sing or dance was seen as virile, and a credit to the species.

It’s very likely that our ancestors saw this musical acumen not just as a skill of entertainment or even enlightenment, but as a way of selecting the most fit partners for mating to in turn give the species the best possible chance of survival. Musical skill was seen with the same level of importance as strength or speed to our forbears.

Fast forward several millennia and music still has the same resonance and impact as it did in our Neanderthal days, but we have stripped away all of the value from it. No longer is musical acumen seen as a critically important trait, it is treated as a lark in the churning belly of our capitalist system. Furthermore, the music and the artists who make it have been devalued so severely that it’s nearly impossible for a professional, working musician to earn a living.

Music is still important. Musicians are not.

Last month I posted a piece about the devaluing of music. It struck a nerve with musicians, devoted fans, and those who are concerned about the state of play for artists in the streaming era. Most responses were supportive and looked for ways to fight the awful pay structure of Spotify and their ilk. Some readers however were quick to point out that they were happy to get their music the cheapest way possible, and they seemed to have little concern for the artists that make the music they love.

As you can see from the comment above, David feels he is only beholden to his own bottom line when making his purchases. That is certainly his right. Based on his answer, it appears that he had invested in physical media before the streaming era, probably because that was his only choice. Now in the age of streaming, he is making the smallest investment that he possibly can to get access to the music that he wants to hear. This is the way the overwhelming majority of people are living today. David claims to be sympathetic to the artist but he is willing to change NOTHING about his behavior to help the situation. He sees it as the musician’s problem.

I’ll grant you that it’s unfair to lay the entirety of this problem at David’s feet. He is simply taking advantage of a terrible situation, as are most listeners. As you read this, ask yourself deeply and honestly how much you have really “invested” in music in the last twelve months. One can literally have ongoing access to the majority of the history of western recorded music for about a hundred bucks a year. That’s a steal, not an investment.

At its core, artist payment is a labor issue. Much like the Asian sweat shops and labor camps that create a wide swath of the clothing and footwear we dress ourselves in each day, Spotify has created an offer that’s too good to refuse. Instead of having governmental oversight or a system that sets up fair payment structures for artists, we have laid the burden once again on the shoulders of the consumer.

If things worked with anything resembling a level playing field, David wouldn't be able to get all of the music he can stand for just ten bucks a month. As it is, the only thing we have to hang on to is the “sympathy” of folks like David. That sympathy is not leading to actual dollars in musician’s pockets.

The current system is also forging a world in which the art that we are making is temporary.

The oldest known cave painting is a red hand stencil in Maltravieso cave in Cáceres, Spain. It has been dated using the uranium-thorium method to be older than 64,000 years. It was made by Neanderthals who were likely very much like the Neanderthals that forged the bone flute found in Germany.

Other cave paintings dating back tens of thousands of years have been found throughout Europe. The earliest paintings like those at Maltravieso were primitive outlines of human hands in varying layers. As the millennia wore on, the paintings became more detailed and varied. Perhaps the most famous example are the caves at Lascaux in southwestern France. There are more than 600 paintings on a series of cave walls that are estimated to be somewhere around 20,000 years old. The paintings, mostly of large animals that occupied the nearby forest, are surprisingly detailed and varied for their early creation.

Long after the homes of these peoples, even the homes of the very wealthiest residents have vanished, their art remains. There is no currency from the era, nor is there any explanation of how their banking or tax systems might have worked. But there was evidence of art and music. Long before we crafted currency, tax structures, bond markets or derivatives, we had art and music.

Much like the bone flute, or the 4,000 year old Sumerian tablets that spell out the Hurrian Hymn, these cave paintings are brilliant relics from a time when art was sacrosanct, and seen as critical to our very survival. Now, we live in an age where it is cheap, ever present, and disposable.

In 4,000 or 40,000 years what will be left to find in our rubble to prove that we were here and that we made beautiful things while we were alive? It is impossible to know what sonic technologies will survive, or if humanity will even endure for more than the short term future. But, as long as we are here we will continue to make and absorb music. It is deep within our very DNA as human beings.

Maybe we should start investing in it like it matters that much.

Cheers,

Matty C

Thanks for highlighting this essay again. I've long credited music as being extremely important to me, but only recently did I fully realize how important.

I didn't study a foreign language in high school, as mine offered only Spanish and French, and I was completely uninterested in both. When I started applying to universities, I realized that was a huge mistake, as several required the study of a second language. My first-choice school accepted my years of band as fulfilling the language requirement, so I owe all of my university education to that fifth-grade decision.

Please do not insult me with these all-or-nothing generalities. Music means different things to different people, and to categorize it as "worthless" is extremely insulting to those who know its true and enduring value.