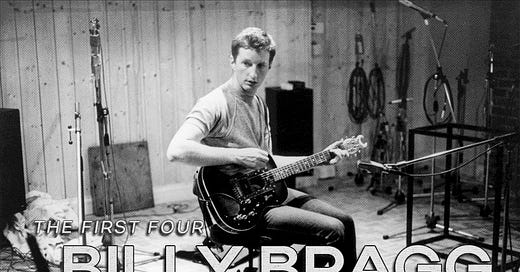

Billy Bragg: The First Four

The quartet of albums that launched the career and causes of a one man version of The Clash.

If you're lonely, I will call

If you're poorly, I will send poetry

I love you

I am the milkman of human kindness

I will leave an extra pint

— The Milkman Of Human Kindness (1983)

Empathy is the engine that drives Stephen William Bragg. Whether he’s singing about the next great political leap forward, or simply “looking for another girl”, Billy Bragg’s heart is firmly attached to his sleeve.

Bragg learned to play guitar at 16 and quickly went on to form Riff Raff, a punk band, with his best mate, Wiggy. After a favorable review in NME of their debut cassette, the band split up and Bragg bounced between odd jobs.

In 1981, with few other options, Bragg joined the army and spent three months in a basic training program as part of a British tank outfit. He loathed it. Upon finishing the initial training, Bragg borrowed £175 from his parents to buy his way out of the remainder of his service contract.

With few other options, Bragg moved back in with his folks in the town of Barking, and began busk…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to What Am I Making to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.